Interpersonal Communication

Learning Unit’s Contents

Interpersonal Communication Defined

In the first leaning module, we defined interpersonal communication as an informal and spontaneous exchange of information between too people, in which none of the speakers has a fixed role (anyone can be sender or receiver of messages).

Of course, this form of communication presupposes a relationship between the people who are involved in the communication.

And RELATIONSHIPS

are defined as any association between at least two people that can be described in terms of intimacy or kinship.

There are, of course, different grades of intimacy or kinship:

Father-son/daughter; brother-sister; husband-wife; friend-friend; teacher-student; boss-employee; etc…

1 – Why Do Humans Communicate

To answer this question, there are several theories.

1.1 The Uncertainty Theory

(Charles Berger & Richard Calabrese)

This theory suggests that we initially meet others when we are attracted to them.

Our need to know about them is the reason why we tend to make

inferences from the physical data that we observe.

Since we feel attracted by them, we have an urge to lessen our uncertainty about those individuals and therefore we look for establishing communication with them.

So according to this theory, we look for communication only with people we felt attracted by. Still, this attraction must not necessarily be physical. We can feel intellectual, or merely human attraction for people. We can feel attracted by people who excel at their jobs, or for people who share our hobbies or values.

1.2 Predicted Outcome Value Theory

(Michael Sunnafrank)

This theory suggests that people connect with others because they believe that rewards or positive outcomes will result.

These rewards might, of course, be ordered in different categories:

There are emotional, economic, affective, safety or entertainment rewards.

1.3 Human Needs

Other authors say

that the interpersonal communication is a way to satisfy our physical and emotional needs.

Abraham Maslow is the most important of these authors.

He classified the human needs in seven categories that have a pyramidal structure, that is, they are ranked in order of priority.

If you analyze the different stages in the pyramid, you will see that the human being uses communication to satisfy each one of our needs.

1.3.1 Physiological Needs

At the bottom of the pyramid Maslow places the PHYSIOLOGICAL NEEDS

That is the need for food, water, sleep, and sex.

They are necessary to maintain life.

1.3.2 Needs for Safety

Once we have satisfied our physiological necessities, safety needs gain importance.

Among these are our needs for physical comfort, stability, order, freedom from violence and disease and security.

According to Maslow, Physiological and Safety needs form the basis of most human motivation.

People have to satisfy these two categories and only after that they care about the higher-order categories.

1.3.3 Needs for Love and Belongingness

Here you have to take into account the needs for friendship, acceptance, approval, and the giving and receiving of affection.

Because of this need, we look for relationships and need the interpersonal communication.

This is also the reason why

we naturally tend to avoid behaviors that would bring us isolation.

1.3.4 Self-Respect

We need an important dose of SELF-RESPECT, to be able to survive.

And how do we get this self-respect? – Of course, we get the self-respect trough the respect of the others. We can respect ourselves only if the others respect us as well.

The need for self-esteem, so Maslow, is a very important motivation to seek out for possible relationships.

1.3.5 Need for Self-Actualization

This need, so MASLOW, represents the desire of self-fulfillment,

the desire to be very best we can be, and to do our very best.

1.3.6 Needs to Know

The needs for knowing and understanding.

We are very curious and that could be a motivation for interpersonal communication.

To reduce uncertainty about others and about the things around us, we have to communicate.

1.3.7 Aesthetic Needs

The need to experience and understand beauty for its own sake.

1.4 Interpersonal Needs

According to William Schutz, there are even specific interpersonal needs.

For this Author,

the interpersonal needs are the most frequent cause and origin of every form of communication.

Schutz distinguishes three categories of interpersonal needs.

1.4.1 The Need for Affection

At the bottom of the pyramid Maslow places the PHYSIOLOGICAL NEEDS

That is the need for food, water, sleep, and sex.

They are necessary to maintain life.

This need is comparable to Maslow’s need for belonging and love.

We need the social warmth, the feeling of being liked or even loved.

We see – almost every day – people joining social groups. They try with that to fulfill this necessity.

In this regard, Schutz differences 3 Kinds of individuals:

The underpersonal individual avoids emotional commitments or involvement with others.

According to Schutz these persons have the need for affection too, but have learned to cover or to hide it.

The overpersonal indivial is exactly the opposite.

They need affection so urgently that they often go to extremes to ensure the acceptance by others.

The personal individual is liked and loved by many and also have fulfilled this need.

1.4.2 The Need for Inclusion

This is basically the need for feeling significant and worthwhile in your social environment.

Here again, Schutz differences three kinds of individuals.

The undersocial individual, like the underpersonal, tries to avoid the communication with others because he or she feels threatened.

They are afraid of attracting the attention to themselves.

Undersocial individuals tend to be shy.

The oversocial individual is the opposite: They need to be the focal point of every meeting.

They can’t keep quite.

They obviously are not afraid of getting the attention, but of being ignored.

The social individual has satisfied his or her need for inclusion and doesn’t need to fall into any these both extremes.

1.4.3 The Need for Control

The need to assert yourself in networks of interpersonal relationships.

Once again, Schutz differentiates three classes of individuals:

ABDICRATS are extremely submissive.

They have the need to be controlled,

frequently because they don’t feel self-confident enough.

The AUTOCRATS are exactly the opposite.

They never have control enough.

They always try to dominate others and to carry through their ideas and their opinions

They tend to show little respect for others.

DEMOCRATS are, of course, in the sound middle.

They don’t feel the need for total dominance,

But the take the responsibility of leadership when it is necessary.

Self-Disclosure

Relationships are always an interaction.

And in each communicational interaction, we disclose information about ourselves, consciously or unconsciously, intentionally or unintentionally.

Communication is never static. And the Degree of self-disclosure varies depending on the situation and on our role in a concrete relationship.

In every relationship there is a tension between the need for privacy and the need for intimacy (self-disclosure).

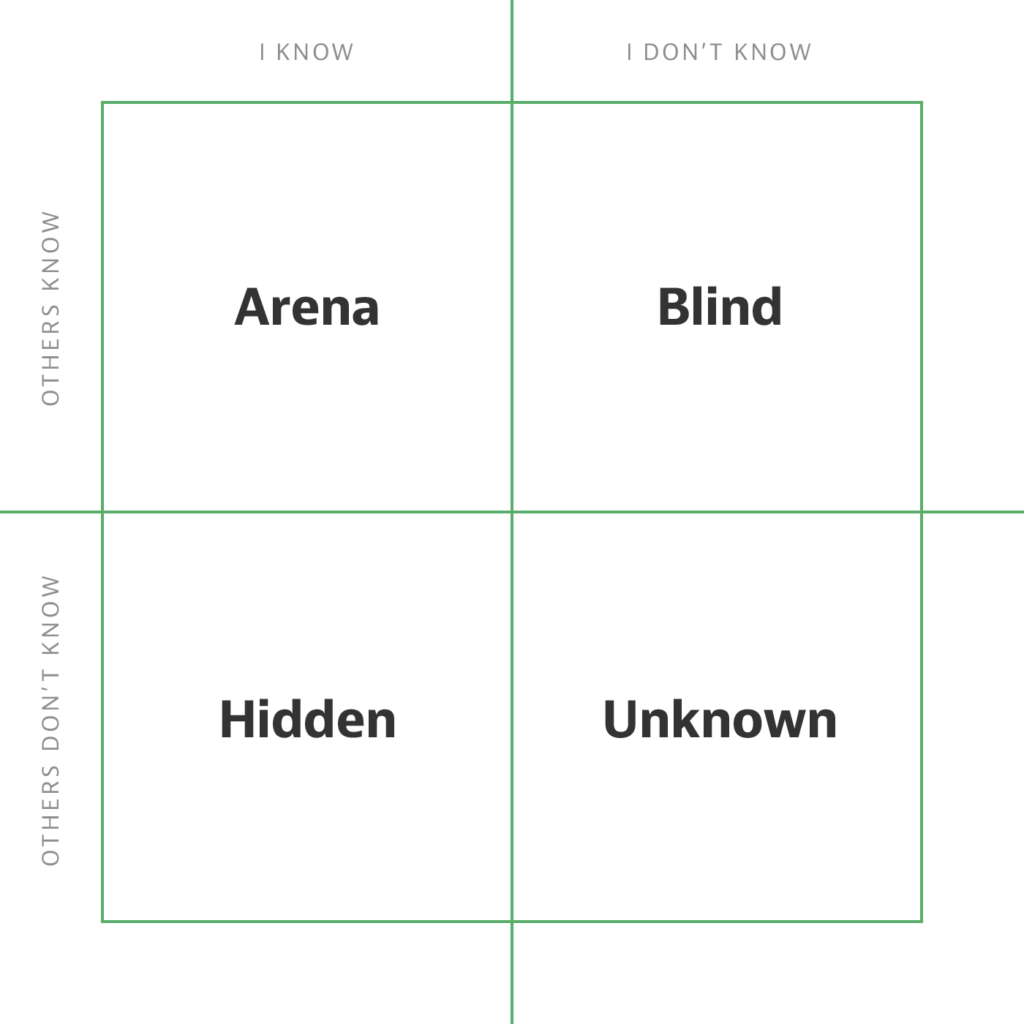

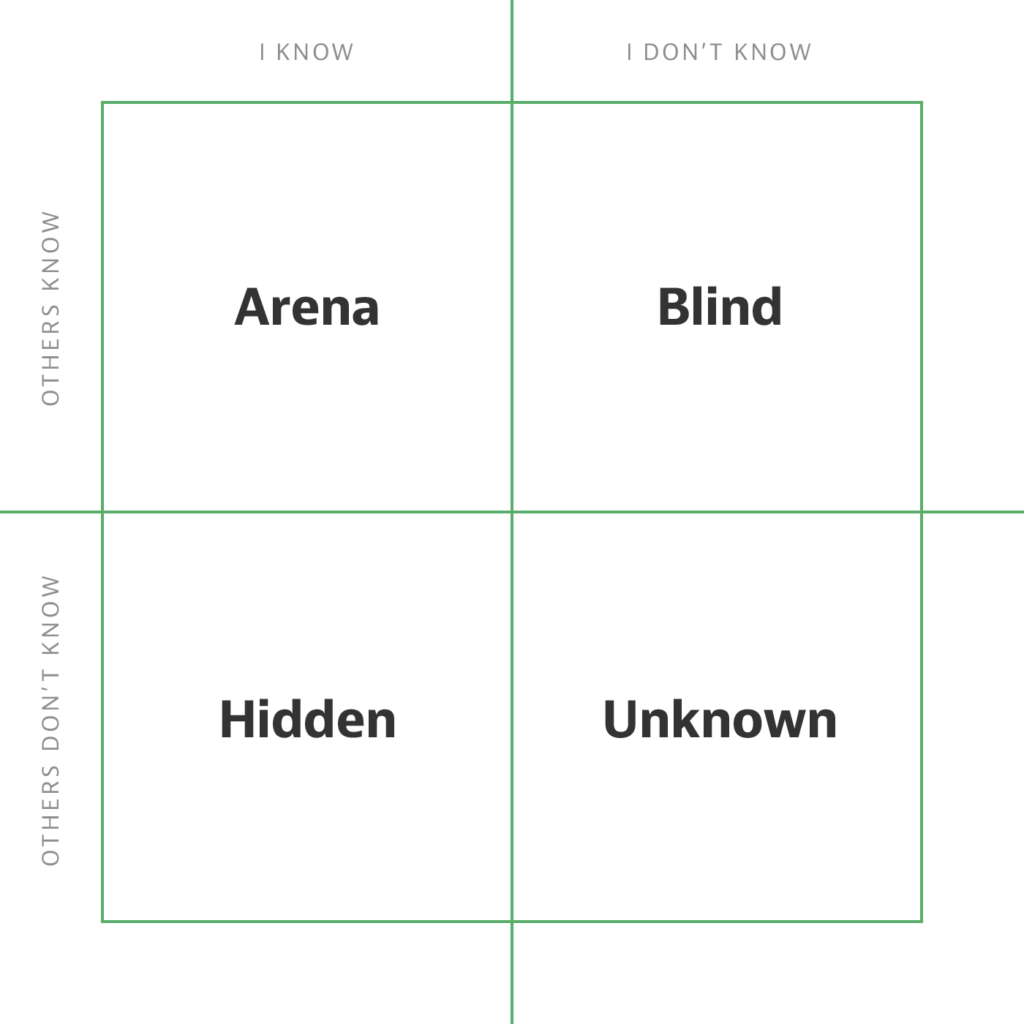

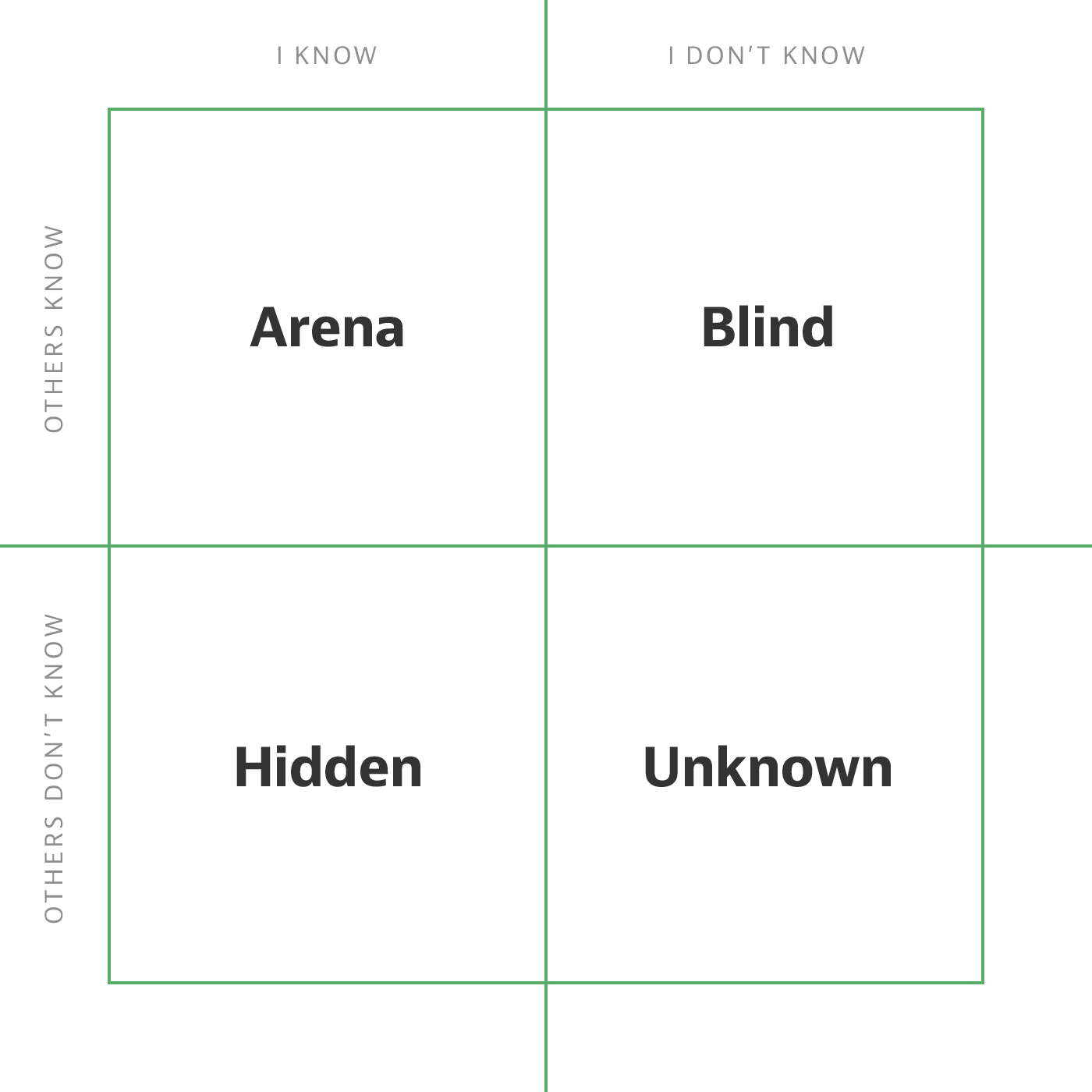

1 – The JOHARI Window

A very popular system of measuring the level of self-disclosure is the

JOHARI WINDOW.

It was called so because the name of the two creators of the idea:

Joseph Luft and Harry Ingram.

The JOHARI window is a very simple matrix based on two coordinates:

- Information known for the individual and the others

- Information not known for the individual and for others

With this matrix,

you can create four areas of information about a person.

These areas of knowledge are not rigid or unchangeable, but flexible.

In fact, they vary in every act of communication.

1.1 The Open Area

First of all, we have the open area. The information of this area is known for us selves and for the others.

It’s evident – that the more intimate is the relationship, the larger this area will be.

1.2 The Blind Area

The blind area includes information that others perceive about us,

But that we don’t recognize about ourselves.

Oversocial individuals, for instance, people who are constantly seeking for attention, may not be aware of this need they have.

1.3 The Hidden Area

The hidden area includes private, very personal information about ourselves,

that we have chosen not to disclose.

Of course, I don’t need to say that the more intimate is the relation ship – and consequently the open area – the smaller is the hidden area.

1.4 The Unknown Area

The last area is the unknown area. And here is contained the information that is not known either for us or for the others.

We repress certain information about us, that might make our lives more difficult because it could be in contradiction with the ideal we have of ourselves.

And this information comes to the subconscious.

For example if we are alcoholics or drug-addicts and we don’t want to admit it, me may tend to hide it not only for others, but for ourselves as well.

This video may help you better understand the Johari Window.

2 – Rhetorical Sensitivity

(Hart, R. / Burks, D.)

Sometimes, wide-open-self-disclosure may be painful or harmful, either for the person who is disclosing him or herself, or for the person who are listening.

Rhetorical sensitivity is simply the tact to choose the right degree of self-disclosure.

Roles and Conflicts

When we are talking about ROLES in relationships, that doesn’t mean that we are acting.

A role is simply a set of norms that condition or even determine your behavior in a concrete social situation.

We have seen several examples of different roles we can play.

In this context is interesting the difference Tubbs makes between

EXPECTED and ENACTED roles.

1 – Expected versus Enacted Roles

Tubbs give the example of a “father”. What you can expect from a father (to care about the needs of his children, to provide financial support and emotional safety for the family, etc)

and how a concrete father really enacts can be totally different – radically different.

We are enacting several roles in our life, and this different roles wake up different feelings and emotions.

Not every student plays his or her role as student with the same intensity – because the motivation can be very different in each case.

Neither the professors play their role with the same enthusiasm and dedication.

2 – Interrole Conflicts

Sometimes,

the reason of the discrepancy between expected and enacted roles is that some of the different roles we play in our life are in conflict with each other.

Tubbs speaks in this regard about interrole conflicts.

I am your teacher (first role),

but I may also be your best friend (second role).

And then if you do a miserable exam, then I have this dilemma: What should I do?

Should I let my friend pass the exam, or should the professor fail the student?

In this video, you can study the consequences of a role conflict in a dramatic situation.

2 – Intrarole Conflicts

Tubbs also speaks about intrarole conflicts. In this case, the conflict arises when two different expectancies are associated to the same role.

Ex. When I said to my mother that I wanted to study in Germany, she had a intrarole conflict.

She knew it could be better for my future,

but on the other hand, she was afraid of the risks of leaving my country at a young age.

Relationships’ Development

(Knapp and Vangelisti’s Model)

There are several scholars who have studied the development of relationships.

They have discovered that relationships have an own dynamic, an own life.

Relationships arise, develop and die.

Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti’s model is the most famous among communication scholars.

They differentiate several stages in the development of relationships.

1 – Stages of Coming Together

1.1 Initiating

In this stage, individuals meet and interact for the first time. A special connection needs to be made in order to motivate one or both of the individuals to continue the interaction. Otherwise no relationship will develope.

1.2 Experimenting

In this stage, the individual takes risks because little is known as yet about the other person. Similarities and common interests are discovered during this stage.

It helps the other person know who you are and provides clues as to how he or she can get to know you better. It establishes the common ground you share with the other person.

These are the kind of question asked in the experimenting process:

- “Who is this person?”

- “What’s your name?”

- “Where are you from?”

- “What’s your major?”

- “Do you know so-and-so?

1.3 Intensifying

This stage marks an increase in the participants’ commitment and involvement in the relationship.

The individuals share more personal and private information about themselves and their family.

Yet, they still keep a certain degree of caution and testing to gain the approval of the other person.

First name or even nicknames start being used.

First person plural (we, our, us) becomes more common.

Private symbols begin to develop, as well as inside jokes.

1.4 Integrating

This stage marks a sense of togetherness.

People in your environment will expect to see you two together, and when they do not, they often ask about the other person.

The partners develop a strong mutual commitment, although they don’t totally give themselves yet.

1.5 Bonding

This is the final stage in the process of coming together, where the relationship reaches the level of development and growth.

The relationship is “public”. Everybody knows.

The relationship at this stage is contractual in nature, even though a formal contract, such as a marriage license, is not required. That means that both partners are aware of the commitments and obligations that the relationship requires.

2 – Stages of Coming Apart

1.1 Differentiating

This is the first stage of coming apart.

Differences between the partners become evident and threaten the development of the relationship.

The communication focuses frequently on how on those differences. And thus, there is a certain degree of anger in the conversations, which become a source of conflict. Knapp and Vangelisti found that the first signs of abuse appear in this stage.

1.2 Circumscribing

The information exchange is strongly limited in this stage. Some topics are completely avoided because both new that they are inevitably a source of conflict.

The quality of the communicative interactions decreases, as well as its spontaneity. Superficiality and tension increase.

Still, the partners try to maintain a harmonic façade in front of family and friends.

Some of the comments that may be heard in this stage:

- “I don’t want to talk about it.”

- “Cant you see that I’m busy?”

- “Why do you keep bringing up the past?”

1.3 Stagnating

The relationship deteriorates rapidly in this stage. The partners avoid communicating, verbally as well as non-verbally.

1.4 Avoiding

In this stage, the partners avoid not only the communicative interaction, but also the physical presence of the other. The emotional distance leads necessarily to separation.

When communication is strictly necessary, the interaction us brief and may be rude.

1.5 Terminating

In this stage, the partners take the necessary steps to make the separation effective and official.

Communication is limited, according to Knapp and Vangelisti, to these areas:

- A summary statement

- Signalizing the termination or limited contact

- Comments about what the relationship will be like in the future, if there is the be any at all

3 – Duck’s Phases of Dissolution

Steve Duck has developed a theory that ony focuses on the dissolution of relationships.

This model is not as deterministic as Knapp and Vangelisti’s model.

There is more uncertainty.

According to Duck, the social environment plays an important role in the development or the failure of relationships.

3.1 Intrapsychic Phase

It is call INTRA-psychic because it occurs inside the individual.

People become aware of their disappointment with the relationship and try to understand what happened, or wonder what may happened in the future.

The communicative interaction decreases. Partners look for relieve outside the relationship.

3.2 Dyadic Phase

The relationship itself becomes an open issue for both partners, and consequently a topic of discussion.

This is the phase of negotiation, persuasion, and argument.

Duck sees this phase as the possibility to save the relationship.

3.3 Social Phase

The issues in the relationship become evident also for outsiders. Family, friends, colleagues are aware that something went wrong.

This Phase comprises Knapp and Vangelisti’s stage of stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

3.4 Grave-Dressing Phase

This phase corresponds to the terminating stage in Knapp and Vangelisti’s model. This is the time in which partners reflect about what is left of the relationship and try to accommodate to it.

In front of the common friends and acquaintances, they justify from their own perspective why the relationship ended.